Garden Fair is back!

Garden Fair is 2021 is set to take place from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Mother’s Day Weekend, May 8 and 9, and we’re looking forward to seeing you (and your Mom) on Mother’s Day Weekend!

Due to ongoing UVA Covid restrictions, Garden Fair will take place at the Clarke County Fairgrounds. The fairgrounds host the Clarke County Fair and other large events, making it a natural fit for Garden Fair. The fairgrounds offer great visibility from Route 7, and plenty of space for vendors and shoppers to spread out.

Admission will remain the same as the last few years, $15 per car. Purchasing admission in advance on our website brings the price down to $10. This is the Foundation’s largest and most important annual fundraiser, providing support to the Arboretum and its many programs.

Preview Night will offer FOSA members first pick of the plants, from 5 to 7:30 p.m. Friday, May 7. The cost is $30 per person before May 5, or $40 per person after that or the day of the event. Anyone who is not a member may join and save 20 percent; this discount applies to renewing members as well.

A great selection of small trees, shrubs, berry bushes, annuals, perennials, and products for your home and garden will please every gardener. Vendors from around the region bring their inventory to Garden Fair. You'd have to drive hundreds, even thousands of miles to enjoy the selection that's available at Garden Fair. Garden Fair is one-stop shopping for everything for your home and garden!

Food vendors will offer lunch while you shop, and covered pavilions provide a place to relax and enjoy a break.

Masks will be required for vendors and shoppers. Smart shoppers bring their own wagons for plants, although we will provide wagons.

The fairgrounds are at 890 W. Main Street in Berryville. For questions, call 540-837-1758 Ext. 224.

BLANDY SCALES DOWN UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH PROGRAM AFTER LAST YEAR’S CANCELLATION

By Kyle Haynes

Associate Director, Blandy Experimental Farm

The Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program, which has been a summertime staple at Blandy since the early 1990s, was canceled in 2020 as the University of Virginia was in “lock-down” in the early days following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sadly, 10 students, who had beaten the odds by being selected over more than 200 other applicants, were informed there would not be an REU program at Blandy for them to attend. Six of the ten students could take some solace in the fact they would be eligible to participate in Blandy’s 2021 REU program. The other four, in contrast, were on track to earn their bachelor’s degrees before summer 2021, which made them ineligible under the guidelines of the federally funded REU program.

The Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program, which has been a summertime staple at Blandy since the early 1990s, was canceled in 2020 as the University of Virginia was in “lock-down” in the early days following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sadly, 10 students, who had beaten the odds by being selected over more than 200 other applicants, were informed there would not be an REU program at Blandy for them to attend. Six of the ten students could take some solace in the fact they would be eligible to participate in Blandy’s 2021 REU program. The other four, in contrast, were on track to earn their bachelor’s degrees before summer 2021, which made them ineligible under the guidelines of the federally funded REU program.

The six eligible students will make up the full complement of Blandy’s 2021 REU students. Amazingly, all six of the star students we admitted for the 2020 program committed to participating in our 2021 program. Under normal circumstances, we train ten students per summer. However, given the need for physical distancing to combat the spread of the COVID-19 virus, there simply is not enough space in Blandy laboratory and housing facilities to accommodate ten students safely. But rather than cancel the program for another summer, the faculty mentors determined to hold a scaled-down program despite the many logistical challenges of adapting a highly interactive, in-person program so that it is safe but still engaging, highly educational, and fun.

The six students who will participate in summer 2021 are enrolled at Rockhurst University (Kansas City, Missouri), Howard University (Washington, D.C.), Worcester Polytechnic Institute (Worcester, Massachusetts), Wheaton College (Wheaton, Illinois), and Mount Holyoke (South Hadley, Massachusetts). You might notice that several of these schools are not major research universities. That is because one of the priorities of the National Science Foundation, which is the sole funder of REU programs across the country, is to provide research experience to students enrolled at colleges that have few opportunities for students to become involved in research. The National Science Foundation’s REU program is seeking to benefit our nation by broadening and strengthening its pool of future scientists.

The six students who will participate in summer 2021 are enrolled at Rockhurst University (Kansas City, Missouri), Howard University (Washington, D.C.), Worcester Polytechnic Institute (Worcester, Massachusetts), Wheaton College (Wheaton, Illinois), and Mount Holyoke (South Hadley, Massachusetts). You might notice that several of these schools are not major research universities. That is because one of the priorities of the National Science Foundation, which is the sole funder of REU programs across the country, is to provide research experience to students enrolled at colleges that have few opportunities for students to become involved in research. The National Science Foundation’s REU program is seeking to benefit our nation by broadening and strengthening its pool of future scientists.

The students entering our 2021 program were given the opportunity to choose among an incredibly diverse set of research topics. These topics include 1) bumblebee foraging patterns, 2) native bee interactions with plants, parasites, and their environment, 3) ecology of aquatic insects and turtles, 4) plant-insect food webs, 5) perceptual and cognitive processes governing egg recognition in wild birds, and 6) ecological and evolutionary responses of plants to differing soil environments. If you are wondering how the few Blandy professors can have the expertise to lead students in such a broad variety of research areas, the answer is they don’t. Four visiting professors from other universities, Mary McKenna from Howard University, Patrick Crumrine from Rowan University, and Rebecca Forkner and Daniel Hanley from George Mason University play critical roles in the Blandy REU program. Not only do they bring their own areas of research expertise, they are also essential coordinators, planners, and workshop instructors.

Amidst uncertain times, the May 17th start date for the summer 2021 program is fast approaching. But the creativity and devotion of Blandy’s staff and faculty will ensure another successful summer research program.

Uncovering a History of Slavery at Blandy, and We’re Just Beginning

By David Carr

Director, Blandy Experimental Farm

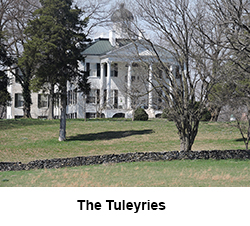

The history of Blandy Experimental Farm is intertwined with an older, crueler history. The property was once a part of what came to be known as the Tuleyries, dating back to Joseph Tuley Sr. in the early 1800s and later Joseph Tuley Jr., his son. In about 1830, it was Joseph Tuley Jr. who commissioned the Tuleyries mansion that stands just west of Blandy. The Tuley family enslaved dozens of people who labored on this land and in their household into the 1860s. The Tuleyries passed through other owners in the time between the end of the Civil War and Graham Blandy’s donation of 700 acres of the estate to the University of Virginia, but we are still trying to reckon with its antebellum history here in the 21st century.

The history of Blandy Experimental Farm is intertwined with an older, crueler history. The property was once a part of what came to be known as the Tuleyries, dating back to Joseph Tuley Sr. in the early 1800s and later Joseph Tuley Jr., his son. In about 1830, it was Joseph Tuley Jr. who commissioned the Tuleyries mansion that stands just west of Blandy. The Tuley family enslaved dozens of people who labored on this land and in their household into the 1860s. The Tuleyries passed through other owners in the time between the end of the Civil War and Graham Blandy’s donation of 700 acres of the estate to the University of Virginia, but we are still trying to reckon with its antebellum history here in the 21st century.

The most obvious reminder of the property’s legacy of slavery is the east wing of the Quarters building, which served as a barracks for many of the enslaved laborers of the Tuleyries. Another part of that legacy has remained hidden from view – an unmarked cemetery located within the Arboretum. We know of the existence of the cemetery from a plat copied in 1925 from a 1904 property survey, but its exact location remained a mystery until recently.

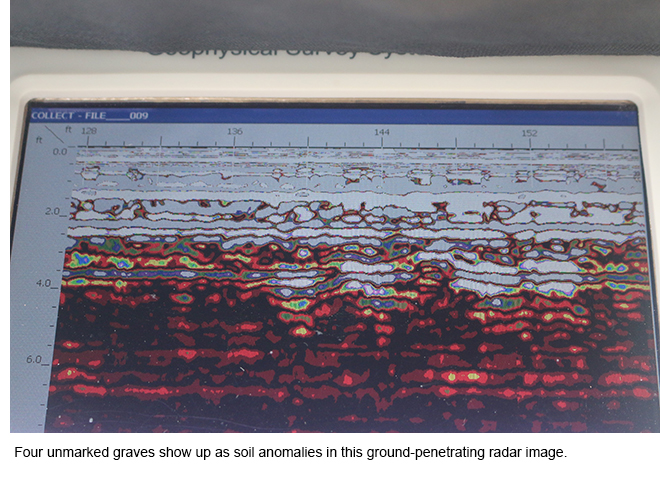

Curator T’ai Roulston was able to use existing landmarks from the century-old plat to develop latitude and longitude coordinates to mark the likely corners of the cemetery. We then contracted with a Leesburg, VA company (GeoModel) to survey the site with ground-penetrating radar. The radar can detect anomalies in the soil structure to depths of about 15 feet. It turned out that T’ai’s translation of the old data was remarkably accurate.

GeoModel was able to detect evidence of 40 graves within the projected boundaries of the cemetery. Outside of those boundaries, the radar detected no soil anomalies, indicating that nobody had ever disturbed the soil to the depth of a typical grave. This gives us reasonable confidence that we were able to detect all of the graves.

With near certainty, given the data collected thus far, each of those 40 graves represents a person who lived and died in bondage, treated as property in life and intentionally left to be forgotten in death. The way that graves are grouped suggests that families perhaps were buried together. They were mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, but we do not know who any of them are. We may never know. But now, they are no longer completely invisible, nor is the shameful history that ties them to this property.

The effort to find these graves is just one of several initiatives we are taking to bring the history of this property to light. We intend to mark the boundaries of the cemeteries and each grave within it. We also will be hiring an intern this summer to help us with archival research that we hope will teach us more about the lives of the enslaved laborers of the Tuleyries. Perhaps our research might someday enable us to identify living descendants and lead to the creation of an appropriate memorial. Our efforts will not provide justice for those who lived and died here, but we will strive to ensure that they are not forgotten.

The effort to find these graves is just one of several initiatives we are taking to bring the history of this property to light. We intend to mark the boundaries of the cemeteries and each grave within it. We also will be hiring an intern this summer to help us with archival research that we hope will teach us more about the lives of the enslaved laborers of the Tuleyries. Perhaps our research might someday enable us to identify living descendants and lead to the creation of an appropriate memorial. Our efforts will not provide justice for those who lived and died here, but we will strive to ensure that they are not forgotten.

We know that much of the history of slavery is scattered and hard to find. If you know about records or family stories linked to the history of slavery at the Tuleyries that you would like to share, we welcome you to contact us.

Fire in the Meadow

Fire in the Meadow

Fire is a great tool for managing native meadow ecosystems. On Wednesday, March 10, we burned about 10 acres of the native plant trail meadow with the help of the Virginia Department of Forestry. In the immediate aftermath, the area looks charred and barren; but in just a few weeks it will be green and teeming with life again!

Connecting Genus to Species: A Hawthorn Problem

By Jared Manzo

Arboretum specialist

The diversity of the arboretum’s plant collection is remarkable.The State Arboretum of Virginia is home to many botanical surprises for our patrons -- some known and some waiting to be found. During my time as an Arboretum Specialist here, I have found the best way to get to know the collection is to follow my curiosity toward the trees that command my attention and draw me near. Not far from our visitor kiosk, suppressed under taller trees, two such specimens reside. Even the most casual observer will pause to appreciate their conspicuous bark and bole morphology: rolling sinuous ribs of exfoliating epidermal patches revealing rusty orange to creamy yellow-orange cork cambium. When I first became curious about these trees, I was disappointed to find the tags only stated the genus: Crataegus or hawthorn. Frustrated by the ambiguity I could not help but think that others had found their path to plant discovery abbreviated. Clearly, I thought, it is a disservice to our visitors to not have an accurate species identification here.

The diversity of the arboretum’s plant collection is remarkable.The State Arboretum of Virginia is home to many botanical surprises for our patrons -- some known and some waiting to be found. During my time as an Arboretum Specialist here, I have found the best way to get to know the collection is to follow my curiosity toward the trees that command my attention and draw me near. Not far from our visitor kiosk, suppressed under taller trees, two such specimens reside. Even the most casual observer will pause to appreciate their conspicuous bark and bole morphology: rolling sinuous ribs of exfoliating epidermal patches revealing rusty orange to creamy yellow-orange cork cambium. When I first became curious about these trees, I was disappointed to find the tags only stated the genus: Crataegus or hawthorn. Frustrated by the ambiguity I could not help but think that others had found their path to plant discovery abbreviated. Clearly, I thought, it is a disservice to our visitors to not have an accurate species identification here.

A quick, inattentive look at these two specimens might suggest they are the same species. When I looked more closely, however, I began seeing differences. For the botanists that study the Crataegus genus, species confusion is common. Reasonable estimates of the number of species globally vary from as few as 35 to more than 100. It was around 1900 that hawthorn species distinctions peaked. The founding director of Harvard's Arnold Arboretum, Charles Sprague Sargent, was particularly scrupulous describing over 700 kinds of hawthorns which included varieties and hybrids. In a 1910 article for the Torrey Botanical Society, Harry B. Brown asked a panel of Crataegus experts how they explain the substantial increase in species. In a rather thorny response, Sargent stated simply that botanists “did not use their eyes.” Amusingly, my college dendrology book, Taxonomy and Ecology of Woody Plants in North American Forests (2002), lacked even a little patience and presented only four species.

To approach a positive identification for these two hawthorns, many of their parts would need to be described and measured. Over the course of a growing season, I compiled notes, at times eye-achingly, on foliar, twig, bud, bark, fruit, and flower characteristics. Leaf characteristics are broken down into four categories: overall shape, margin, apex, and base morphology. This allowed for an exciting foray into botanical descriptors. A section of my notes on foliage for one specimen reads, “broadly ovate to deltoid with lacerate margin; 5-9 lobes (11 rarely); base truncate/attenuate; apex broadly acute to obtuse. “ Now, if you can picture the leaf based on the above description, congratulations; your command over plant glossaries is enviable.

To approach a positive identification for these two hawthorns, many of their parts would need to be described and measured. Over the course of a growing season, I compiled notes, at times eye-achingly, on foliar, twig, bud, bark, fruit, and flower characteristics. Leaf characteristics are broken down into four categories: overall shape, margin, apex, and base morphology. This allowed for an exciting foray into botanical descriptors. A section of my notes on foliage for one specimen reads, “broadly ovate to deltoid with lacerate margin; 5-9 lobes (11 rarely); base truncate/attenuate; apex broadly acute to obtuse. “ Now, if you can picture the leaf based on the above description, congratulations; your command over plant glossaries is enviable.

Comparing the two specimens, it was clear they differed in seed, leaf, flower, and form characteristics. With plant profiles in hand, I began reviewing the various taxonomic literature we have in our library to locate the proper species. The first stop, obviously, was Sargent’s Silva of North America (1947) which is a 14- volume behemoth featuring full-page illustrations for each plant. This reference brought me close to a positive identification, but it lacked notes on flower stamen and pistil counts as well as nutlets per fruit. A visit to Sargent’s more modest publication Manual of Trees of North America (1905) did include this information which gave me the confirmation I needed. One more thing: internet resources regarding potential species were unsatisfactory and sometimes inaccurate. The point here is to seek out multiple sources and judge them against one another when dealing with a challenging plant identification problem.  Based on sample descriptions and reference materials, I was able to identify these two hawthorns as littlehip hawthorn (Crataegus spathulata) and parsley hawthorn (Crataegus marshallii). And I must say, the plant parts described fit the reference material very closely. There were no variations that would have forced me to wade into the historically murky waters of Crataegus speciation. Two littlehip hawthorns dwell in the picnic grove. The common name refers to the pomaceous fruit resembling a much smaller version of a rosehip. Three parsley hawthorns are located between the Parkfield Learning Center and a retired greenhouse. The common name for this one refers to the leaf’s resemblance to the flat-leaf parsley herb. Both hawthorns are native to southeastern United States in coastal and river flood plains with parsley hawthorn being a rarer Virginia native. Curiosity led to discovery which led to state champion recognition as well as propagation of these specimens by seed for the next generation.

Based on sample descriptions and reference materials, I was able to identify these two hawthorns as littlehip hawthorn (Crataegus spathulata) and parsley hawthorn (Crataegus marshallii). And I must say, the plant parts described fit the reference material very closely. There were no variations that would have forced me to wade into the historically murky waters of Crataegus speciation. Two littlehip hawthorns dwell in the picnic grove. The common name refers to the pomaceous fruit resembling a much smaller version of a rosehip. Three parsley hawthorns are located between the Parkfield Learning Center and a retired greenhouse. The common name for this one refers to the leaf’s resemblance to the flat-leaf parsley herb. Both hawthorns are native to southeastern United States in coastal and river flood plains with parsley hawthorn being a rarer Virginia native. Curiosity led to discovery which led to state champion recognition as well as propagation of these specimens by seed for the next generation.

Take a closer look for science! Springtime observations

By Emily Ford

Lead Environmental Educator

With spring season approaching, many of us notice crocus buds poking up through the soil, opening their petals when warmed by the sunlight. Or the ever-so-slight color change as tightly packed buds of red maples begin to loosen and reveal their bright red flowers. Or hearing the familiar song of our favorite migratory bird. Or watching bees emerge to gather pollen from early-blooming flowers. All of these provide hints that spring is approaching. Engaging in making these close observations is at the heart of phenology.

With spring season approaching, many of us notice crocus buds poking up through the soil, opening their petals when warmed by the sunlight. Or the ever-so-slight color change as tightly packed buds of red maples begin to loosen and reveal their bright red flowers. Or hearing the familiar song of our favorite migratory bird. Or watching bees emerge to gather pollen from early-blooming flowers. All of these provide hints that spring is approaching. Engaging in making these close observations is at the heart of phenology.

What is phenology? It is the study of the timing of the life cycle events of organisms. Phenologists use observations and careful data collection of life cycle events to learn more about how plants and animals interact with one another, the world, and abiotic factors (temperature, wind, length of day for example). Data acquired through phenological observations over time help us understand how plants change over the seasons and how plants respond to long-term changes in climate. Scientists use data about various species to make predictions about how habitats and ecosystems might change in the future.

What is phenology? It is the study of the timing of the life cycle events of organisms. Phenologists use observations and careful data collection of life cycle events to learn more about how plants and animals interact with one another, the world, and abiotic factors (temperature, wind, length of day for example). Data acquired through phenological observations over time help us understand how plants change over the seasons and how plants respond to long-term changes in climate. Scientists use data about various species to make predictions about how habitats and ecosystems might change in the future.

Recent studies, such as this one based on Thoreau’s comprehensive journals, compare naturalists’ phenological observations from the past with current phenology data to investigate the impacts that climate change is having on species, habitats, and ecosystems.

Want to get involved? Two of the larger community science phenology monitoring organizations are Project Budburst and National Phenological Network. Simply snapping photos and uploading to iNaturalist provides data to scientists. One of the best things about phenological observation is that everyone in a community can participate. Children of all ages, individuals, families, school groups, etc. Once you get a feel for either of the above projects, it is easy to contribute to the community science data set. I invite you to get in touch with me (emilyford@virginia.edu) for ideas and advice on how to create phenology projects for PK-12 students (whatever the setting: in-person school, at-home virtual learning, home school cooperatives, or a nature-centric caregiver)!

Join in the Observation Fun!

https://budburst.org/activities/for-families.

Project Budburst has created numerous activities for families, the following two are perfect to do while exploring at Blandy.

Crocus Counting is good for younger scientists, with a focus on easy-to-find, early spring flowers. (Don’t worry, you can observe daffodils or dandelions instead if you missed the crocuses).

With the Flower Power Activity, families can compare two flowers to develop deeper observation skills.

There are other great options for backyard explorations and gardening too.

Choose an activity, get outdoors, take time to be in nature, and start observing!

Botanical standouts enjoy celestial stardom

By Tim Farmer

Public Relations Coordinator

Not many trees have traveled beyond the confines of Planet Earth, but a few have the cosmic distinction of boldly going where no tree has gone before.

Not many trees have traveled beyond the confines of Planet Earth, but a few have the cosmic distinction of boldly going where no tree has gone before.

This year is the 50th anniversary of NASA’s Apollo 14 mission, which is probably best remembered as the time astronaut Alan Shepard hit a golf ball on the surface of the moon. But according to NASA, on that same mission, fellow astronaut Stuart Roosa packed hundreds of tree seeds into his personal gear.

Roosa was a former U.S. Forest Service “smoke jumper,” fighting forest fires in areas virtually inaccessible except by parachute. Forest Service Chief Ed Cliff knew Roosa and asked if he would take some tree seeds into space to determine whether the journey had any effect on their viability. (Spoiler alert: It didn’t.) Nearly 500 seeds made the trip, comprising five tree species: loblolly pine, sycamore, sweetgum, redwood, and Douglas fir.

Roosa, the pilot of the Command Module “Kitty Hawk,” and his botanical cargo orbited the moon 34 times while fellow astronauts Shepard and Edgar Mitchell walked on the moon, NASA history recounts. Upon their return to earth, the seeds were distributed to Forest Service offices in California and Mississippi. Most of the seeds germinated successfully and were given to other state forestry organizations, often as part of the nation’s bicentennial celebrations in 1976. Two Moon Trees (as they became known) ended up in Virginia, a sycamore in Hampton and a sweetgum that’s probably closer than you think.

Roosa, the pilot of the Command Module “Kitty Hawk,” and his botanical cargo orbited the moon 34 times while fellow astronauts Shepard and Edgar Mitchell walked on the moon, NASA history recounts. Upon their return to earth, the seeds were distributed to Forest Service offices in California and Mississippi. Most of the seeds germinated successfully and were given to other state forestry organizations, often as part of the nation’s bicentennial celebrations in 1976. Two Moon Trees (as they became known) ended up in Virginia, a sycamore in Hampton and a sweetgum that’s probably closer than you think.

According to a 2005 story in the Loudoun Times-Mirror, the sweetgum was struggling to survive and in 1978 it was given to then Deputy Chief of the Forest Service Max Peterson of Leesburg, who nursed it back to health. Peterson planted the tree on private land just east of Hamilton, in nearby Loudoun County. The land later became part of a large commuter parking lot, but the tree was protected by a stone wall and enclosed in a wire fence. An interpretive sign explains its star power.

To find this celestial traveler, take Rt. 7 east to the Rt. 704 exit, and bear right off the exit ramp. Turn left at the stop sign at East Colonial Highway (also known as Business Rt. 7). After about a mile, turn left into Scott Jenkins Memorial Park. Bear left, and the tree will be on the right, surrounded by a stone wall. Look for the interpretive sign.

Although a number of the Moon Trees have died, more than 50 survive and their locations are documented. Others have been lost, so if you are aware of any of their locations, NASA wants to hear from you. If you know of a Moon Tree, please send a message to dave.williams@nasa.gov.

Learn more about other Moon Trees below.

NASA’s story of the Moon Trees, including a list of their locations, is here: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/moon_tree.html

Second-generation Moon Trees are available for purchase here: https://americanheritagetrees.org/product/msu-moon-tree/

Quarters photo takes top award

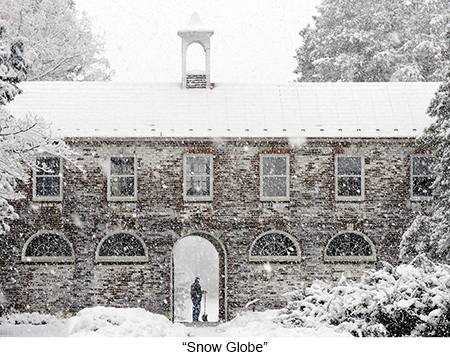

A photo of the Quarters building in a snowstorm recently earned first place in the Clarke County Easement Authority’s “A Snapshot in Time” photo contest.

A photo of the Quarters building in a snowstorm recently earned first place in the Clarke County Easement Authority’s “A Snapshot in Time” photo contest.

Public Relations Coordinator Tim Farmer took the photo of John Campbell, Custodial Service Coordinator, as he was shoveling the Quarters walkway in January 2020.

The photo, titled “Snow Globe,” was selected from 115 images by 26 photographers. Another of Tim’s photos, “Just One More,” earned an honorable mention.

The contest asked photographers to submit images taken outdoors in Clarke County during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tim said he thought the photo depicted the isolation many are experiencing during the pandemic.

Ken Garrett, whose photography has appeared in National Geographic, Smithsonian, Air and Space, Archaeology, Fortune, Forbes, Time, Life, Audubon, GEO, National Wildlife, and Natural History magazines, served as judge. Garrett said it was difficult to narrow down the winners. “There was a lot of very nice material, and it was challenging to select the top three and a short list of honorable mentions.”

Garrett also awarded honorable mentions to images by Bre Bogert, Bryce Bogert, Colby Bogert, Lauren Dilzer, Christy Dunkle, Barbara Hughes, Cathy Kuehner, June Krupsaw, Warren Krupsaw, Pam Lettie, LaDawn Presgraves, and Dawn Webb.

Garrett also awarded honorable mentions to images by Bre Bogert, Bryce Bogert, Colby Bogert, Lauren Dilzer, Christy Dunkle, Barbara Hughes, Cathy Kuehner, June Krupsaw, Warren Krupsaw, Pam Lettie, LaDawn Presgraves, and Dawn Webb.

As judge, Garrett looked for images that best convey the coronavirus reflected in outdoor activities, isolation, or open spaces in Clarke County. He also focused on content, contrast, composition, and creativity.

Since its creation in 2002, the Clarke County Conservation Easement Authority has placed more than 8,000 acres into conservation easement, retiring 275 dwelling unit rights. When included with other entity holdings, such as the Virginia Outdoors Foundation, over 26,000 acres — more than 23 percent of the county — are protected in perpetuity.

For more information about the Conservation Easement Authority, its photo contest, or conservation easements, contact Clarke County Natural Resource Planner Alison Teetor at 540.955.5134 or ateetor@clarkecounty.gov, or visit clarkelandconservation.org.